John Collier wrote an article in 1929, entitled “Amerindians,” which used measured language and concrete statistics to paint a sober picture of American Indians’ well-being. According to Collier’s figures, the number of Indians who lived in the U.S. had fallen from approximately 825,000 at the time of America’s discovery by Europeans, to 350,000 at the time of his writing.

Day school was mandated for children aged six to eighteen, and they had to go to boarding schools away from their families if there were no acceptable schools nearby. Collier noted that “the food allowance for the children is eleven cents a day, supplemented in a few cases by provender from school gardens and dairies.”

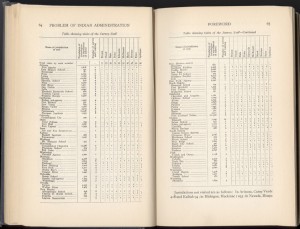

The 1925 census showed a 62% increase (28.5 per 1,000) in the death rate of Indians over the previous five years. This figure showed that the Indians’ death rate had surpassed their birth rate. The Bureau of Indian Affairs disputed the census findings, but according to the article, admitted that the Indian death rate was about 95% higher than the general death rate.

________________________________________________________________________