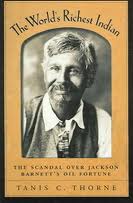

Indians who couldn’t speak English were easy targets for whites who wanted their assets. A bit of mental deficiency only made it easier. Jackson Barnett was a retarded Indian in Oklahoma who received a randomly selected allotment (160 acres) around the turn of the 20th century. When oil was discovered on the land, the Indian Office appointed a guardian for him; the guardian very properly leased Barnett’s land for him and paid the oil royalties to the superintendent of the Five Civilized Tribes at Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Indians who couldn’t speak English were easy targets for whites who wanted their assets. A bit of mental deficiency only made it easier. Jackson Barnett was a retarded Indian in Oklahoma who received a randomly selected allotment (160 acres) around the turn of the 20th century. When oil was discovered on the land, the Indian Office appointed a guardian for him; the guardian very properly leased Barnett’s land for him and paid the oil royalties to the superintendent of the Five Civilized Tribes at Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Jackson was eventually worth over a million dollars, and in 1920, a white woman suddenly showed up on his doorstep and persuaded him to get into her car. She drove Barnett to Kansas and married him (against Kansas law), then drove to Missouri and married him again. She eventually got him to sign over half his money to a mission society, and half to her.

This woman and others concerned with Barnett’s estate met with Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, who gave his approval for their actions. Publicity eventually upset the wife’s plans and the courts threw out the contracts Barnett had signed. Burke was criticized for his actions, but he was exonerated of wrong-doing by the House subcommittee which investigated the case.

______________________________________________________________________________________