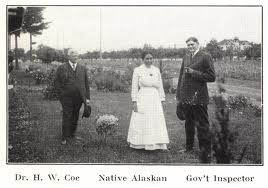

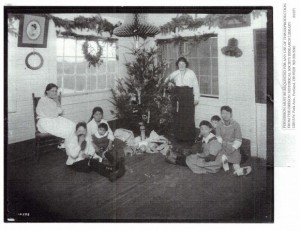

Like other institutional staff, employees at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians demonstrated a wide range of ability, attitude, and character. Inspectors sometimes complained that employees weren’t always available when needed; sometimes that happened because the employee was shirking his or her duty. More often, however, there just weren’t enough employees to cover all the work that needed doing, plus provide the necessary patient supervision. During the next few posts, I’ll talk about the work situation and some of the employees at the asylum.

One of the first employees to make a stir at the asylum was Dr. John Turner. He was not from Canton, and felt strongly that superintendent O. S. Gifford favored the rest of the employees (from Canton) over him. Turner complained that the attendants often ignored his orders, and that Gifford didn’t back him up. When a patient became pregnant because employees hadn’t followed Turner’s instructions during his absence, he filed a complaint in December, 1906, with the supervisor of Indian schools, Charles Dickson. Turner’s complaint resulted in Canton Asylum’s first major (and negative) inspection.

______________________________________________________________________________________