Once asylum superintendents gained a measure of respect and prestige (see last post), they used their power to secure their positions within both the medical community and their own specialty. They wanted no meddling or advice from outsiders–especially non-medical outsiders–and fought against any kind of oversight that involved community laypeople. Boards comprised of leading citizens often oversaw the running of asylums, but many times they acted as rubber stamps for whatever the superintendent decided was best. Superintendents could accept a few suggestions, of course, but they particularly resented laypeople making any kind of staff appointments. They did not want to see superintendent or assistant superintendent positions filled through committees of laypeople or appointed by the state governor. Instead, these specialized alienists wanted to establish and maintain a closed circle of “members” who controlled all aspects of asylum management.

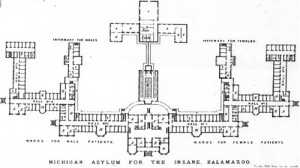

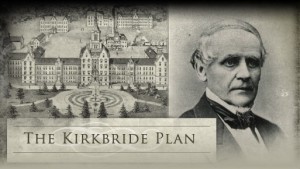

This attitude marked their whole approach to management. Besides being very involved with the architectural details and physical construction of the asylum (superintendents were often appointed well before an asylum opened), superintendents imposed their own treatment philosophy on their institutions. “One man, one rule” defined their medical attitude–they wanted all decisions to go through them. They were usually quick to dismiss suggestions from patients’ families, even though these people undoubtedly had valuable insights to offer. This top-down, “I’m the expert” attitude was firmly entrenched by the time the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians opened, and its patients were in a particularly poor position to have their voices accepted.

______________________________________________________________________________________