Solstice celebrations (see last post) helped peoples in cold areas of the world cope with their fear that summer would never return to a dark and dreary world. Later, these celebrations acted as bright spots during a long season of inactivity and discomfort. Wintertime was certainly a period of discomfort for most people, and could be deadly without proper shelter and enough food. South Dakota, where the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was located, was no exception. Though records were not kept throughout the state’s (and territory’s) history, we do know that the state’s lowest recorded temperature reached 58 degrees below zero on February 17, 1936, in McIntosh. (Its highest was 120 degrees in Gannvalley that same year–representing a 178 degree swing in temperatures.) There is no way to know what wind chills may have been, since these measurements were not widely used by weather reporters until the 1970s.

Blizzards were a particular hardship on the Plains and in the Dakotas, where few trees could stop the wind and blowing snow. Frigid temperatures throughout winter often killed livestock, and indoor temperatures sometimes could not get above freezing. Milk, water, and even the ink in inkwells froze, and sometimes children stayed in bed all day simply because it was too cold to get up. Meanwhile, parents prepared food in freezing kitchens as they remained dressed in outside winter gear. Blowing snow could both blind and suffocate people, and settlers often strung clothesline between their houses and barns to prevent losing their way and dying of exposure. Winter in the Dakotas was a fearful time that left bitter memories for many families.

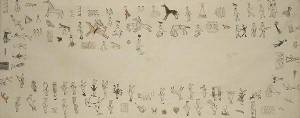

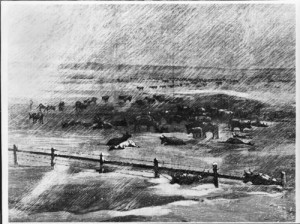

Photo of a Drawing by Charles Graham of a Herd of Cattle in a Blizzard, courtesy Kansas Historical Society

______________________________________________________________________________________