Like most other societies, Native Americans usually incorporated well-defined gender roles within their various groups. Men hunted, fought in battle, negotiated treaties and agreements, and made decisions about moving. Men were chiefs, medicine men, and priests, though women could also take on these roles at times.

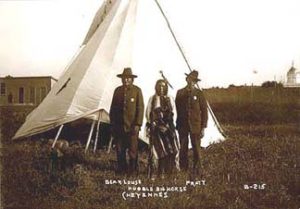

Women raised children, farmed if the society were agricultural, tanned skins and preserved food. Though their home-making roles were similar to white women’s, Native American women typically had more power. In Cherokee society, women owned land. Plains Indians traced their lineage through their mothers. Iroquois women controlled their families and could initiate divorce, and Blackfoot women owned the tipi in which their families lived. One important difference between Native American and white societies was the respect women received for their contribution to the home.

________________________________________________________