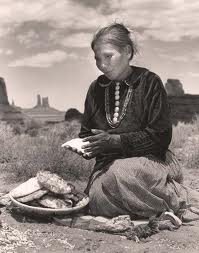

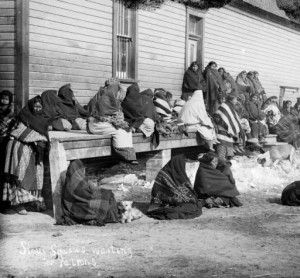

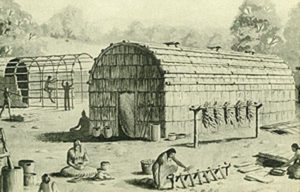

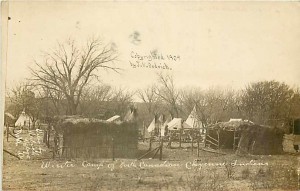

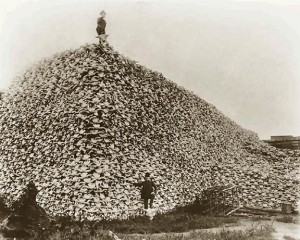

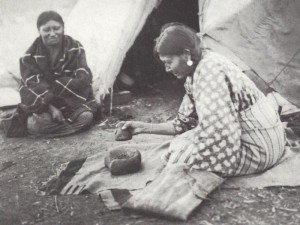

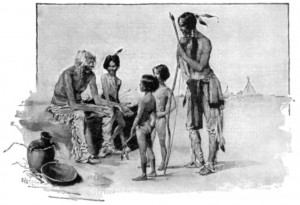

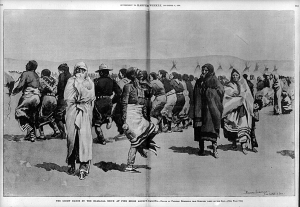

When settlers arrived on Native American shores, they met robust nations with well-developed cultures and survival systems. However, native peoples did not domesticate the animals they ate to any great extent, nor grow food crops as extensively as Europeans did. Unfortunately, settlers considered animal domestication and agriculture hallmarks of civilization; they immediately assumed that the indigenous peoples they met had not yet “risen” to their own level. Much of the interference in native culture practiced by the U.S. federal government and by religious groups targeted this perceived lack of civilization.

In doing so, these groups delivered some of the most devastating blows to Native Americans possible. Official insistence on European-style farming in particular brought ill-health and suffering to Native Americans. Tribes that were pushed to unfamiliar, marginal lands in the West could not live on what they raised by farming. Federal food allotments were necessary for survival, but the allotments also were inadequate. Poor-quality beef, flour, sugar, and coffee could not replace the superior nutrition that game, fish, and the varied plants gathered from large swaths of land, had previously provided. Health problems quickly surfaced, and soon the federal government and Native Americans became mired in a system that could only react to the worst of any number of crises.

______________________________________________________________________________________