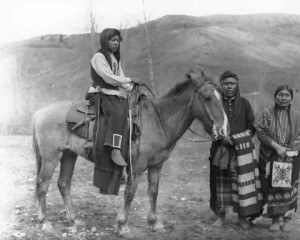

Native American tribes pursued different lifestyles depending on where they lived. Though most did not farm in the European sense of having large, established plots owned by one owner/family group, farming was a well-developed practice in many areas. Native Americans typically moved their farming operations every few years, allowing their agricultural land to regenerate after intense use. New plots had to be prepared from either virgin wilderness or substantially overgrown land, so preparation was started far in advance of any actual shift to a new field.

Men first girdled trees by chopping bark all around the trees’ bases; the trees eventually rotted and fell or dried out and stood in place. Men returned to the area at least a year later–perhaps more–and gathered all the brush and fallen wood. They piled this material along with chopped saplings around the trees which had dried in place, and set fire to it. Though the method sounds wasteful today, it actually fertilized the earth with rotted wood and ash. The method also saved a great deal of labor, since girdling and burning trees was much easier than chopping them down and hauling them away.

The communal culture of most tribes usually carried over to farming, so these large fields would have provided food for everyone. Family groups may have also worked smaller plots for personal use.