O.S. Gifford

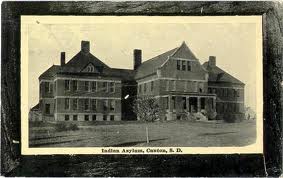

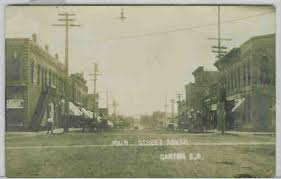

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was too small to compare to the large institutions created by Kirkbride, and it wasn’t built with any particular treatment plan in mind. Its first superintendent, O.S. Gifford, (see 2/25/2010 post) was not even a medical man. He had to travel to Washington, D.C. to see an example (St. Elizabeths) of the kind of institution he was to run.

Canton Asylum was a two-story building with four wings, and had a seven-foot fence around it. In keeping with other government institutions of its kind, however, it was lushly landscaped with over 1,000 trees and bushes that in time looked lovely.

Because Gifford wasn’t an alienist, he defaulted to a type of moral treatment that consisted of giving patients chores to do, allowing them to fish and play games when possible, and even allowing them to act like Indians. He allowed native dancing except when it proved too much for excitable patients, and let women create beadwork. This was in direct contrast to most governmental attitudes toward Indians.

His laissez-faire approach both helped and hurt the patients at Canton Asylum. Though he had no pet psychological theories to impose, he also couldn’t be bothered with setting up real programs to enable cures. When patients ran away or became hard to handle, his staff just got out the shackles.

Beaded Vest (1890-1900), courtesy Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library

Tobacco Bags (1895) courtesy Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library

________________________________________________________