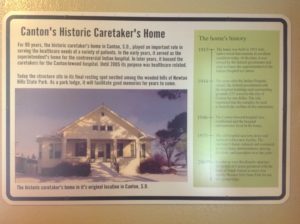

Soon after he took office, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work contacted the Institute for Government Research; he wanted them to take an intensive look at how his organization was managing the Native American population under its control. The Institute gathered a team of experts headed by Lewis Meriam to survey reservations, schools, and other Indian Bureau facilities. On February 21, 1928, they presented Work with a report called “The Problem of Indian Administration” that didn’t mince words.

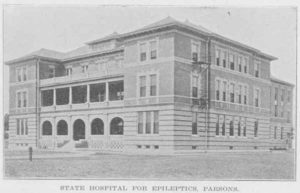

Meriam’s report reviewed the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, and found it lacking. By this time, the institution had several buildings, and the report began with a brief description of them: “At Hiawatha (the local name for the asylum) . . . the central portion of the main building contains the administrative quarters and the culinary section on the first floor, and the employees’ living quarters on the second floor.”

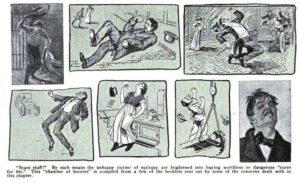

The bakery was located in the basement of the building and “was in disorder and the oven was in a bad state of repair.” The inspectors noted the sleeping arrangements for patients and said that: “Equipment is confined almost entirely to iron beds.”

It was a dismal picture, and it seemed consistent. “The hospital building is located about fifty yards from the main building. On the first floor is a good sized dining room in great disorder.” It added later, “The dairy barn was very disorderly,” and that “the power plant and laundry are located in a separate building . . . both were in disorder.”