The world changed rapidly in the early 20th century, and the Roaring Twenties seemed to kick up the excitement. Movies had enhanced America’s entertainment options (see last post), but more serious achievements also promised to push boundaries. Two researchers from Canada, Frederick Grant Banting and Charles Herbert Best, had discovered the hormone, insulin; diabetics now had a chance to lead normal lives. That same year, Albert Einstein received a Nobel prize for discovering the theory of relativity, while Adolf Hitler became leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party. In the U.S., Alice Mary Robertson became the second female congresswoman and the first woman to defeat an incumbent congressman; the Black Sox trial began in Chicago; and race riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma left 60 blacks and 21 whites dead.

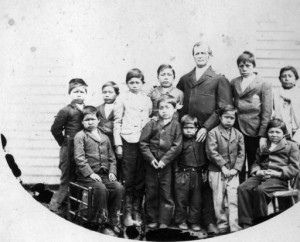

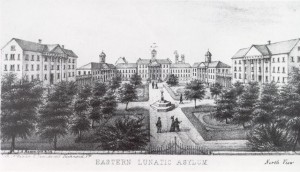

At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, Dr. Harry Hummer was trying–as usual–to expand. He was of the opinion that hundreds of insane Indians among the reservation population were not able to receive proper care for their problems. He based his assumption on insanity rates derived from census reports, and was probably correct that all insane Native Americans among a population of over a quarter million, were not currently patients at his asylum. However, when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs asked for a list of applicants for admission to the asylum (Hummer always implied that a horde of applicants had to be turned away), Hummer could only give him 35 names.

______________________________________________________________________________________