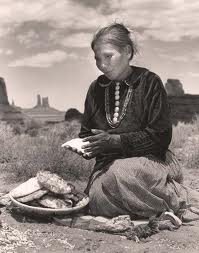

When the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians had a small patient population, physical care was very likely good. The asylum’s physician, Dr. Turner, had as thorough a knowledge of general medicine as any other regional practitioner, and was enthusiastic about working in Canton’s unique facility. He gave patients standard medications (see last post) for their physical ailments, and both he and the asylum’s superintendent set up a system of mental health treatment similar to those in other asylums. Able-bodied patients worked in the gardens and took walks outside, while women more typically helped in the dining room and kitchen, cleaned floors, and went to classes which Turner referred to as “numbers” and “object lessons.”

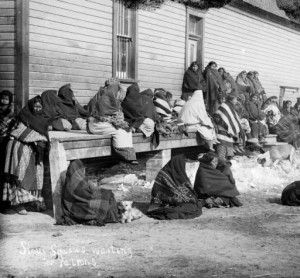

The asylum’s report for these activities was dated August 29, 1903. A report from another South Dakota agency (Indian Training School, Yankton) made by James Staley that same year, indicates a number of health problems for residents there. Dr. O. M. Chapman, the agency physician begins: “The health of these people has been just about that of the average of former years.” Though he noted that contagious diseases were not a problem–except for a few cases of measles–he also stated that the number of people were declining since there had been 68 deaths and only 60 births. Forty percent of the deaths had been due to tuberculosis, which Chapman called “alarming.”

“The death rate was about 40 per 1,000,” Chapman says. “This is a death rate at least four times what it would be among an equal number of whites.”

Group Picture at the Phoenix Indian School Tuberculosis Sanitorium Phoenix, AZ, circa 1890-1910, courtesy National Institutes of Health

______________________________________________________________________________________