Annuity payments could be a time of festivity (see last post) even though merchants and alcohol traders were often on hand with bad deals for Native Americans with spending money. Ration disbursements, though also eagerly anticipated, could be an opportunity for outright fraud at the hands of the people trusted to make them. Continue reading

Author Archives: Carla Joinson

Payments on Reservations

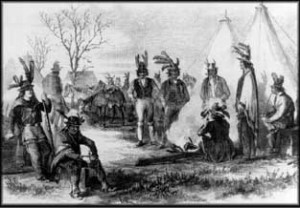

Treaties between the U.S. government and Native Americans almost always stipulated annual payments of money and/or goods to tribes which had signed the treaties. On most reservations, one day was set aside for these annuity payments, and that specific day became known as “payment day” for money annuities and “ration day” for annuities paid in goods. Payment Day could become quite an event. Almost every Indian on a reservation came to the payment place, usually the Indian agency. The agency consisted of an office building, employee housing, storage, barns, etc.; it was also (usually) under military protection and so included troop quarters and military storage buildings.

Knowing that Indians would have money on Payment Day, traders in all sorts of goods flocked to the agency and displayed their merchandise. Sometimes as many as 100 traders showed up, and their wares were geared toward merchandise they knew their customers wanted. Grains, cooking pots and pans, washtubs, coffee mills, calico and muslin, blankets, saddles, bridles, jewelry, and so on were offered, and the exchange sometimes became a festive, two-to-four day event. Unfortunately, rum and whiskey peddlers set up their stations close by as well, and many Indians fell prey to intoxicants that perhaps led them to spending extravagances.

Reservation Food

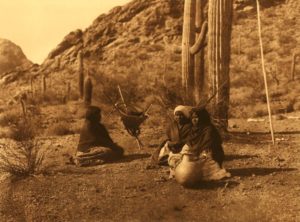

Sioux Women Receiving Rations, courtesy Denver Public Library, Colorado Historical Society, and Denver Art Museum

Native Americans ate what was on hand in the regions where they lived. (See last post.) Once they were forced onto reservations, their freedom to secure food was severely reined in. The government began to issue rations, partly in recognition that much of reservation land was too poor to support the people who lived on it. Food was also a powerful weapon to hold over Indian heads; if they wanted to eat, they needed to comply with the new rules and ways of life the government wanted to introduce.

Rations typically included flour, tea, coffee, salt, beans, and other staples, as well as dry goods like blankets. Beef replaced buffalo as a meat source, and Native Americans learned to cook new foods which were drastically different and of inferior nutritive value to their traditional foods. Poor nutrition inevitably led to poorer health and a worsened quality of life. These forced changes undoubtedly left many psychological scars on the adults who saw their entire way of life change.

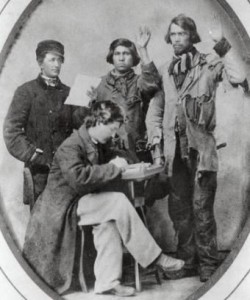

Modoc Men Slaughtering Cattle (includes Indian Agent Col D.B. Dyre) around 1870-80, courtesy Library of Congress

_________________________________________________________

Changes in Native American Diet

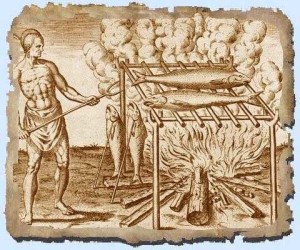

Traditional Native American diets depended upon the foods available regionally, with some tribes depending primarily on hunting and others on agriculture. Most foods were minimally processed and fresh, though dried foods certainly played a part in winter provisions. Besides game and fish, Native Americans ate maize (an early type of corn), beans, squash of all kinds, wild rice, sweet potatoes, and tomatoes, cacti, and chilies among other richly nutritious items. Eggs, honey, and many nut varieties rounded out this ancient diet.

Native American diets were extremely low-glycemic (the glycemic index of a food is a measure of how fast its energy is absorbed into the bloodstream) and high fiber. Karl Reinhard, a professor of forensic sciences at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says that ancient foods may have been 20-30 times more fibrous than today’s. Native Americans may have actually consumed 200 to 400 grams of fiber a day–an extreme deviation from today’s recommendation of 25 grams of fiber for women and 38 for men and just about impossible to replicate using today’s modified food. Once Native Americans lost their ability to eat traditional foods, they quickly became susceptible to disease and ill health, particularly from diabetes.

More Food Changes

Issuing Flour to Ojibway Woman, White Earth Reservation, 1896, courtesy University of Minnesota, Duluth

As Native Americans were forced onto reservations, they were also forced to abandon their healthy diets of fresh meat and produce in favor of canned goods and poor-quality staples. Their experience has ultimately been echoed throughout the country as people nearly everywhere have drifted away from home-grown food in proper quantities and introduced processed and/or GM (genetically modified) food into into their diets.

Corn has been hybridized so much that it is no longer the same product that Native Americans and European immigrants ate; modern genetic modifications have made this food a poor nutritional choice. A study from the Permaculture Research Institute on non-GM corn and Roundup-Ready corn, found that the GM corn contained glyphosate and formaldehyde at toxic levels. This corn was also seriously deficient in nutrients: non-GM corn had over 6,000 ppm (parts per million) of calcium, while the GM corn had 14; other nutrient levels were similarly affected.

Native Americans and other concerned consumers are trying to introduce non-GM corn back into the food system. Heirloom varieties like White Flint Hominy (also known as Seneca Hominy or Ha-Go-Wa) are hundreds of years old; Ha-Go-Wa was recently harvested by tribal seed savers associated with the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. Many heirloom varieties produce colorful, intensely flavorful corn–just not as abundantly as the hybridized type which replaced it.

Recipe For Disaster

Native Americans generally ate a healthy, varied diet when they were free to do so. Foods included wild berries, fishes of all kinds, pigeons and ducks, bread made from nutritious wild grasses like pigweed and dropseed, and sweeteners from agave and maple syrup. Native Americans drank sassafras tea and broth thickened with corn silks, along with many other soups and drinks. Many explorers were impressed by the physical development of Native Americans and saw much to admire in their athleticism and endurance. Continue reading

Spring Planting

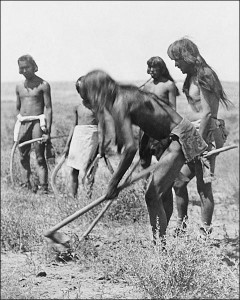

Native American tribes pursued different lifestyles depending on where they lived. Though most did not farm in the European sense of having large, established plots owned by one owner/family group, farming was a well-developed practice in many areas. Native Americans typically moved their farming operations every few years, allowing their agricultural land to regenerate after intense use. New plots had to be prepared from either virgin wilderness or substantially overgrown land, so preparation was started far in advance of any actual shift to a new field.

Men first girdled trees by chopping bark all around the trees’ bases; the trees eventually rotted and fell or dried out and stood in place. Men returned to the area at least a year later–perhaps more–and gathered all the brush and fallen wood. They piled this material along with chopped saplings around the trees which had dried in place, and set fire to it. Though the method sounds wasteful today, it actually fertilized the earth with rotted wood and ash. The method also saved a great deal of labor, since girdling and burning trees was much easier than chopping them down and hauling them away.

The communal culture of most tribes usually carried over to farming, so these large fields would have provided food for everyone. Family groups may have also worked smaller plots for personal use.

Division Doesn’t Stop with the U.S.

During the Civil War, Native Americans fought for both the Confederacy and the Union. Tribes found it difficult to decide which government to trust, since their experience had shown that almost all white men in policy-making positions were untrustworthy. Not all tribes were united in or satisfied with their leaders’ decisions, but Native American soldiers could be depended upon to fight bravely and remain loyal to the cause they had chosen.

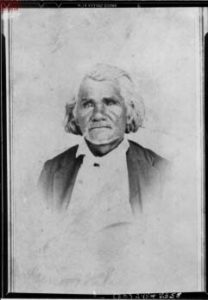

Stand Watie was born in 1806 in present-day Gordon County, Georgia. He signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1836, in which a group of Cherokees surrendered their land in the east in exchange for land in the west (Oklahoma). Because he had signed this treaty and given away tribal land, Watie was under a death sentence from the group of Cherokees who had disagreed with the decision. During the Civil War, Watie accepted a commission as colonel in the Confederate States Army and raised the First Regiment of Cherokee Mounted Volunteers. (Watie became principal chief of the western Cherokee when Chief John Ross abandoned the Confederacy.) Watie successfully harassed Union forces and captured the Union steamboat, J.R. Williams. He was promoted to brigadier general in May, 1864.

Ely S. Parker was born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Indian Reservation (Seneca nation) in New York. Parker became a successful engineer and received an appointment from the Treasury Department to oversee the construction of a custom house and marine hospital in Galena (Illinois). There he met Ulysses S. Grant; during the Civil War, he served on Grant’s personal staff and became his military secretary in 1864. (Parker copied the terms of surrender given to Robert E. Lee at Appomattox.) When Grant became president of the U.S., he appointed Parker as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the first Native American to hold that position.

Native American Participation in the Civil War

Nearly 8,000 Native Americans joined the Confederate army to serve during the Civil War. The Confederacy actively pursued Native Americans to join its cause against the Union, and signed several treaties with members of the Five Civilized Tribes. Native Americans also chose to support the Union and joined its army as well, but they were not recruited with the same focus and enthusiasm.

Union leadership relocated the country’s current soldiers serving in Indian Territory to what they considered more critical areas, leaving this vast expanse of land wide open for skirmishes. The Union’s abandoned forts were immediately appropriated by the Confederacy, which was also anxious to use the Territory as a buffer zone for Texas and Arkansas, a possible link to the western part of the U.S., and a resource to mitigate the consequences of a possible Union blockade.

Though Indian Territory did not suffer combat on the magnitude and frequency of Confederate states like Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia, several important clashes occurred:

* Battle of Round Mountain

* Battle of Pea Ridge

*Battle of Honey Springs (the largest in Indian Territory). This battle occurred in July, 1863 and resulted in a decisive Union victory which gave it control of Indian Territory.

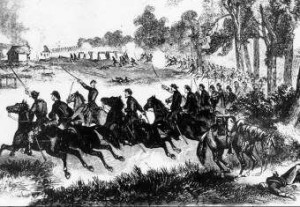

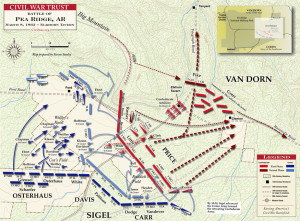

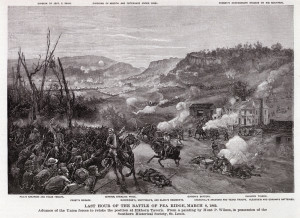

Battle of Pea Ridge

Knowing that Native Americans were bound to have little loyalty to the United States, the Confederacy wanted to enlist their aid during the Civil War (see last post). In 1861, Brigadier General Albert Pike was assigned to the Department of Indian Territory and charged with recruiting and leading Native Americans disaffected with the current Union government. Pike believed that his Indian recruits would serve best while remaining in Indian Territory, but his superiors ordered him to bring 2,500 men into Arkansas. Pike brought a force of about 800 or 900 men and subsequently engaged in the Battle of Pea Ridge (March 6-8, 1862). Very little went well for him in this clash, and the action may have served to show Confederate leaders that attorneys without military experience do not make good generals.

Pike and the Cherokee troops surprised a two-company column of Iowans and successfully routed them early in the battle. The Confederate soldiers celebrated jubilantly, throwing the area into confusion. During the confusion and emotional turmoil of the battle’s aftermath, Cherokee troops scalped at least eight Union soldiers. Later, Generals Benjamin McCulloch and James McIntosh were killed during the battle. Colonel Louis Hébert brought a large force of about 2,000 men to the battle, but got lost in the woods in a poorly executed drive against outnumbered Union forces. Because of poor leadership, General Pike did little to keep the Rebel force moving toward victory. The battle was decisively lost to the Union, and this loss contributed to Missouri being secured for the Union. Pike resigned his commission in 1862 and was indicted in Federal court for inciting war atrocities.

(The Battle of Pea Ridge was also called the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern.)