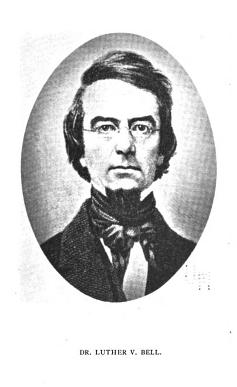

One early alienist was Luther V. Bell (1806-1862) . He was only 30 years old, and Superintendent at McLean Asylum, when the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane first met. Bell observed many cases of insanity at McLean, and wrote about a new form of mania which had formerly been associated with typhoid fever.

Patients were unable to sleep, paranoid in the extreme–often believing their food was poisoned–and frantically violent. Most of the sufferers were strapped into beds so they wouldn’t attack anyone. Bell observed that the patient’s recovery was often as quick as the onset of the condition had been. Most people were well within 3-4 weeks.

Though this condition may seem like a pure example of pseudo-psychiatry as practiced in the early days of alienists, Bell’s Disease has never been dismissed as an erroneous observation. In1981 the term excited delirium was introduced in the Annals of Emergency Medicine to describe this state.

In my next post I’ll describe some of the ways that alienists devised to keep patients quiet when they were in a excited state.