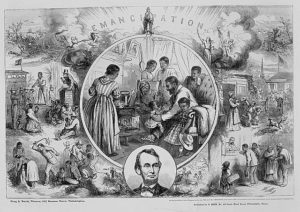

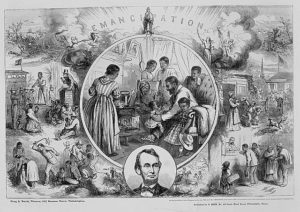

Emancipation, created by Thomas Nast, 1865, courtesy Library of Congress

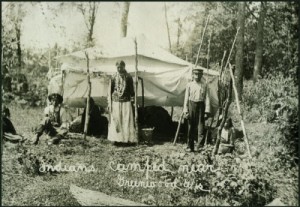

Most alienists believed that insanity was higher among “civilized races” than the more barbaric ones like Negroes and Indians. The theory was that people who didn’t live under the pressures of civilization, with its myriad choices, stresses, and striving, didn’t usually fall prey to mental problems.

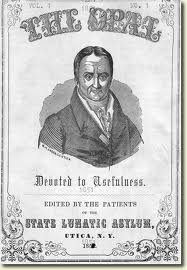

Slaves Working, With Overseer

When slaves were set free after the Civil War, the treatment of insane Negroes in asylums increased. Dr. William F. Drewry, the superintendent of Central State Hospital in Virginia wrote a paper detailing the reasons for freedom’s disastrous results:

1. Before emancipation, the freedom from care and responsibility, the plain, wholesome, nourishing food, comfortable clothing, open air life, and kindly care when sick, acted as preventative measures against mental breakdown in the negro.

2. The negro, as a race, was not prepared to care for himself or to combat the new problems in his life.

3. Hereditary deficiencies and unchecked constitutional diseases and defects, transmitted from parent to offspring, play now a hazardous part in the causation of insanity and epilepsy in the race.

The article did conclude that “the greater number of insane negroes come from the uneducated, thriftless classes…a well nourished, intelligent, thrifty negro, leading a correct life, is probably little more liable to become insane than a white person under similar condition, except for the fact that the powers of resistance and endurance are weaker in his race than in the white race.”

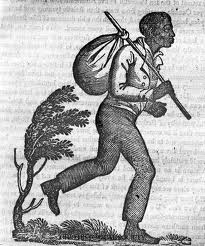

Male Slave Rushing Hot Food From Kitchen to Main House, courtesy xroads.virginia.edu

________________________________________________________