Patients Seated in Dining Room at Pennhurst, circa 1915, the Former Eastern Pennsylvania Institution for the Feeble Minded and Epileptic

When The Problem With Indian Administration was delivered to the Secretary of the Interior by Lewis Meriam’s team (see last post), the report made many recommendations for the hundreds of schools, reservations, and hospitals the team had visited. These included increasing salaries of personnel who had direct contact with Indians (to attract better people to the Indian Service), more cubic feet per child at boarding schools, and adopting the standards established by the American College of Surgeons for accredited hospitals to all Indian Service hospitals.

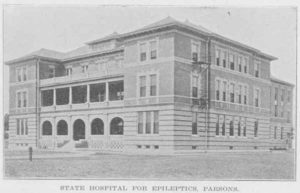

The team recommended several specific improvements for the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians: Increase the personnel; put a graduate nurse in charge of each building with patients; provide additional laborers for the farm and dairy; segregate epileptics, children, and the tuberculous into three groups apart from the other patients; and improve equipment in the hospital, kitchen, and bakery. The team included a call for installing “a system of records conforming to accepted psychiatric practice in hospitals for the insane.”

Children’s Dayroom at Byberry, Later the Philadelphia State Hospital,, circa 1938, courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Dr. Harry Hummer, superintendent at the Canton Asylum, did try many times to get a separate cottage for epileptic patients, but was never successful. However, a later inspector who was a psychiatrist–which no one on Meriam team had been–believed that most of the patients with convulsions were not even epileptic. Meriam’s team likely had to go by Dr. Hummer’s diagnoses, in which he had identified any patient with convulsions as epileptic.