Dr. Harry Reid Hummer was born in Washington, DC in 1878. When he and his wife, Norena, arrived in Canton, South Dakota, they had two young sons: Francis, and Harry, Jr. They later had a daughter who died shortly after birth. Hummer’s ambition may have been a good role model for his sons. Harry Jr. attended the Naval Academy and rose to the rank of rear admiral in the U.S. Navy, and Francis became a doctor.

Most of Hummer’s extended family resided in the east. He had a brother (Washington, DC) and sister (Silver Spring, Maryland) who survived him, as did his wife. When Hummer died in 1957 at the age of 79, he also had four grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

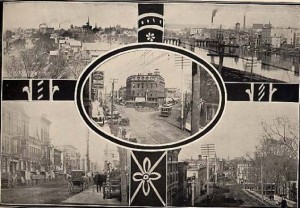

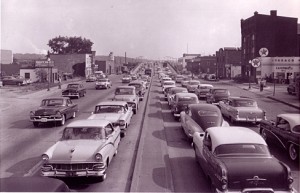

South Capitol Street, circa 1957, courtesy District Dept. of Transportation Historical Photo Archives

______________________________________________________________________________________