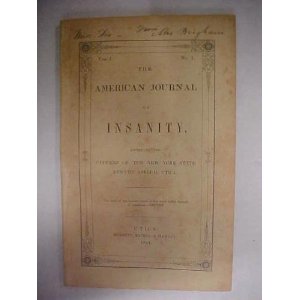

Asylum superintendents tended to support each other and their profession, and presented a united front to the public. Though they published studies and treatment-oriented articles in the American Journal of Insanity (AJA) and other medical organs, the AJA in particular reflected much of their philosophy.

In a July, 1868 article, “Admission to Hospitals for the Insane,” the author contended that it was especially unkind to make the insane endure a public hearing on their sanity. “If we find a man sick or wounded in the street, we take him forthwith to the nearest hospital, without stopping to canvass our legal right to restrain him of his liberty,” the author stated.

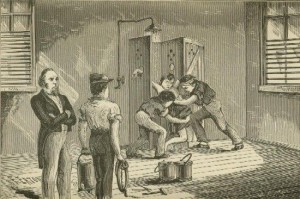

With the insane, however, relatives force publicity by requiring “an inquisition to establish the delirium or the lunacy,” the article continued. He said that there was no more reason why a magistrate or civil authority should inquire into treatment [for an insane person] than there was to “rescue a patient from the hands of a skillful surgeon who is binding him to an operating table to perform an amputation.”

This article is only one instance of an ongoing disagreement between the psychiatric profession and private citizens about the value of admitting (or coercing) patients into asylums without due process.

______________________________________________________________________________________