Native Americans resisted white encroachment on their lands and cultures in a variety of ways (see last two posts). They refused to cooperate with these intruders, refused to send their children to their schools to learn new ways, and held on to their traditions by many strategies. One other significant way Native Americans resisted settlers was to join forces with their enemies. This occurred during the Seven Years War (1754-63) when Britain and France fought over New World territory with the help of native peoples on both sides.

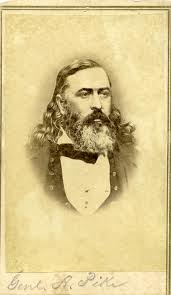

By the time the American Civil War began, Native Americans had had experience with the treachery and false promises of the federal government. Officials in the Confederacy approached various native peoples to remind them of this, offering them better opportunities under Confederate rule for their help in fighting Union forces. The Confederacy created a Bureau of Indian Affairs in March, 1861 and appointed David L. Hubbard as its commissioner. In 1861, the new country’s leaders commissioned attorney Albert Pike as a brigadier general and assigned him to the Department of Indian Territory. There, he was to raise regiments among the Indians and command them in battle. My next post will discuss Native Americans and the Confederacy further.