Though early alienists did a great deal to de-stigmatize insanity and help families feel better about seeking help for their mentally ill members, insanity was still a delicate subject that most families preferred to keep private. Asylum superintendents understood this.

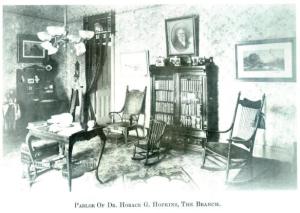

They tried to be as soothing and discreet as possible, often bringing families into nice parlors for a private chat to quiet their embarrassment and fears and to find out more about the patient’s problem. Many asylums also had fences around them, not just to keep patients inside, but to keep the curious public out while patients walked or worked on the grounds.

When patients were transferred from one asylum to another, as often happened when a new asylum opened to alleviate overcrowding, the public usually came out in force to watch the transfer. When the East Tennessee Insane Asylum received fifty female patients from the Nashville institution, the Knoxville Daily Journal (March 21, 1886) said that, “The curiosity of about one hundred men, women and children, who had hovered around Erin station all yesterday afternoon was gratified when the train of female lunatics arrived at 4:00 o’clock.”

A few weeks later, the same paper ran an article about two new patients–referred to as inmates–brought to the asylum. A woman was brought by her daughter, and a man by the sheriff of Campbell county. A third person who had gone “crazy about religion” had been tied hand and foot in a train that then passed through town on its way to Wytheville (Virginia) where the man was to be incarcerated. He was accompanied by two sisters and a brother, but spent his time sitting in his seat “singing, cursing and gesticulating frantically.”

The paper called the latter a sad case, but went ahead and printed the man’s name–as well as the names of the other two patients–and as many details about them as it could. It surely did not make anything easier for these patients or their families to receive so much publicity about a situation they would rather have remained private.