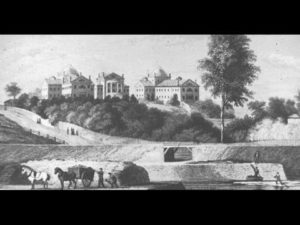

Charity Hospital in New Orleans

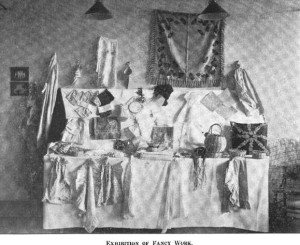

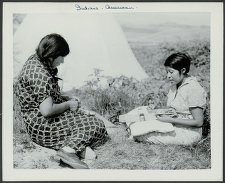

Most asylums used work therapy both to save labor costs and as occupational therapy for patients. Patients typically cleaned/straightened their rooms, worked in the gardens, sewed, and performed other ordinary chores involved in running a large, self-sustaining establishment. Some institutions went a little further.

In Louisiana before the Civil War, several dozen insane patients were cared for in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans. When the legislature finally established a separate asylum for them (East Louisiana Hospital for the Insane in Jackson), it appropriated only $10,000 per year to support the entire institution and the 85 patients transferred to it in 1848.

Patients began their chores there, and some of the men worked in the brick yard for six to seven hours a day. By 1879, patients had made 225,000 bricks at a cost of $2/thousand. The bricks were used for additional buildings, which were required as increasing numbers of patients from Louisiana and surrounding states were admitted. Before the turn of the century, patients had made 2,200,000 bricks.

Brickmaking Around the Turn of the Century

East Louisiana Hospital for the Insane

________________________________________________________________________