Even when overcrowding and underfunding began to eat away at the effectiveness and relative comfort of asylum care, superintendents often went to great lengths to create a festive atmosphere during Christmas and other major holidays. These efforts eased the monotony of asylum life for patients as well as for staff.

At Northern Hospital for the Insane, staff decorated the chapel with a Christmas tree and placed evergreens and candles throughout the room. Many patients had received presents from their friends and family, and the superintendent, Dr. Wigginton, and his staff had purchased additional gifts to place under the tree so that no one would be forgotten.

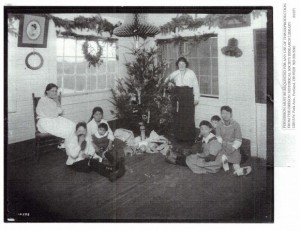

Christmas at Morningside Hospital, Portland, Oregon, circa 1920s, courtesy Oregon Historical Society

At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, patients also celebrated Christmas with a decorated tree, special meals, and stockings filled with edible treats. In 1927, the asylum received additional holiday help from the Chilocco, Oklahoma YWCA; its girls gathered (and likely contributed) gifts like dolls, games, and books to the asylum’s patients as a service project. These were delivered on Christmas Eve, to the delight of the patients. Hummer asked the coordinator to continue with the service project, and the girls evidently did so, since there is record of the asylum receiving gifts again in 1932 or 1933.