Athens Female Ward, 1893, courtesy Athens County Historical Society and Museum

Going to an asylum was psychologically difficult at the best of times, but women could be expected to suffer a bit more . . . after all, many asylum patients had been homemakers unused to much interaction outside their own houses. Ironically, the paternalistic society in which women lived, with all its “protections” gave them few skills to cope with sudden changes to their routines and environments. Of course, women have responded heroically to all sorts of negative situations, but it seems reasonable to assume that between the two genders, women would have been less exposed to communal living and interactions with strangers during the 19th century. In general, women had been taught to seek protection and rely on others, and to find their satisfaction in home, family, and close friends. Their feelings of abandonment and friendlessness upon entering an asylum would be dependent upon how strongly they had adhered to this “womanly” ethic.

A letter from Mary Page to her sister (in 1871) speaks to the anguish many forgotten women felt:

“It has been a long and trying time since I saw or heard from you or any of the rest of your family or any of my relations. . . . Almost four years have this band of enemies been at work on me with foul play . . . . You all can pity my condition and picture to yourselves my sad fate all too unjustly committed. I have never given anyone in this whole world the first cause for themselves to fight poor me . . . ”

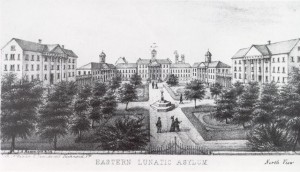

The letter is written from Williamsburg Hospital in Virginia, probably referencing Eastern Lunatic Asylum. Though the letter is somewhat rambling and makes a series of bitter comments and accusations against “unjust enemies” (which may have been the result of hallucinations/paranoia and the reason for her commitment), the woman’s pain is evident. Undoubtedly men were sent to asylums and forgotten, too, but given their social conditioning, women would have felt it more keenly.

Eastern Lunatic Asylum

Female Department, Michigan Asylum for the Insane, 1892, courtesy Kalamazoo Public Library

______________________________________________________________________________________