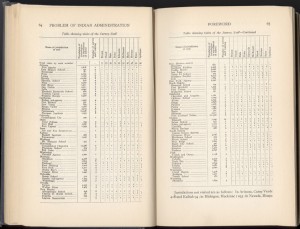

St. Elizabeths and the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were investigated a number of times during the early twentieth century. Both were federal insane asylums, but they were also quite different. St. Elizabeths was very much a medical facility, while the Canton Asylum was run along Indian boarding school lines. In 1927:

— St. Elizabeths had an amusement hall (Hitchcock Hall) for patients; Canton Asylum did not.

— St. Elizabeths had specialized buildings like cottages for tubercular patients and quarantine buildings; Canton Asylum did not.

St. Elizabeths had a 10,000 volume library and subscribed to 35 periodicals; in 1925 the Congressional Library began to send its surplus magazines to the asylum (about 1,000 a month); Canton Asylum received subscriptions to about half a dozen magazines.

St. Elizabeths had a furlough program which allowed patients to go home on trial visits; a social worker followed up on patients during these short visits; Canton Asylum actively discouraged furloughs for any reason. St. Elizabeths created an out-patient department for veterans who had been discharged from the military shortly after commitment. This department helped some patients find employment and tried to help them find a home so that they would not be overwhelmed when they were released. Canton Asylum did not help its patients this way.

A typical menu for a Tuesday midday meal at St. Elizabeths showed: bean soup, beef pot roast, gravy, browned potatoes, cucumbers, bread, oleo, and tapioca cream pudding. A menu for Canton Asylum (from the 1928 Meriam Report) showed: a stew of meat and carrots, with more fat and bones than anything else, thin apple sauce, bread, and coffee.

St. Elizabeths was significantly larger than the Canton Asylum, which gave it justification for some of its specialized facilities. However, its placement in Washington, DC and its patient population (veterans and citizens of the District of Columbia) also mattered. The American Red Cross, veterans’ groups, and the Knights of Columbus, as well as other civic organizations had easy access for volunteer work and aid of various kinds; the Canton Asylum had to depend on the kindness of small-town organizations like volunteer ministers and the Canton Band to help its patients.

However, both organizations had areas of weakness that investigations brought to light.