Even in modern societies with their convenient grocery stores, many people continue to can or dry food from their gardens for winter use. Canning was not an option for native peoples, but they still needed to preserve food for times when game was scarce and/or vegetation was sparse.

There were few universal preservation practices, but drying food was an option available to almost everyone. Drying also had the advantage of making the harvest easier to store and transport: Drying not only concentrated nutrients, but the resulting product also weighed less because so much water was lost in the process. Some foods like beans could dry naturally on the vine, but other foods like corn, berries, and mushrooms were usually gathered first and then dried. Sun-drying was one way to preserve all types of food.

Over thousands of years, Native Americans cultivated a wild grass called Teosinte, which originally grew in Central America. Over time the small kernels on this grass became larger and were spaced closer together until what we know as maize developed. These first ears were only a few inches long and had about eight short rows of kernels (today’s ears have about 600 kernels). Eventually maize became an important food source for many tribes.

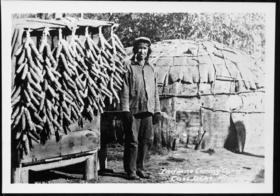

Native Americans grew corn in mounds and harvested great quantities of it, compared to other gathered foodstuffs. They dried maize in the sun on mats, let the maize dry on its stalks, or picked ears and let them dry in the sun. Drying was essential because the loss of moisture made it harder for microorganisms and enzymes that spoil food to grow. Later, the maize would be stored in underground pits lined with grass to prevent mildew and spoilage; some tribes stored enough to get them through two crop-less seasons.

Ojibwa Farmer Near Cass Lake, Minn. Drying Corn Harvest, circa 1920, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

______________________________________________________________________________________