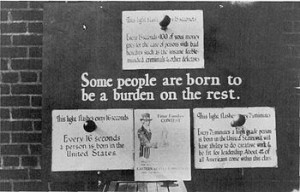

Dr. Harry Hummer’s concern about releasing female patients of childbearing age (see last post) shows that he was looking at factors beyond a patient’s ability to live comfortably outside asylum walls. Hummer was neither alone nor unusual in his concern that a former female patient might bear a child who would, in turn, inherit the mother’s problem. (For some reason, he did not voice the same concerns about male patients.) Both anecdotal observation and real scientific research over many years had made it clear that certain genetic traits could be inherited. A fear of inherited insanity was of long standing, and featured as a theme in a number of Victorian novels in which characters refused to marry because of the “taint of insanity” running through their bloodline.

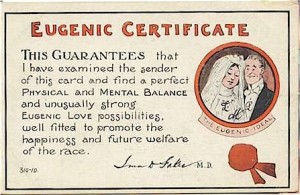

The rising popularity of eugenics (the theory and practice of improving the genetic quality of a population) during the turn of the century and into the 1930s, gave validity to concerns about inheriting madness. Researchers in eugenics tended to believe that many human qualities–good or bad–were inherited rather than the product of environment. Their pseudo-science was well-presented, however, and many people believed that almost anything could be inherited. Even before Hummer became the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians‘ superintendent, Americans had begun to support the idea of sterilizing so-called “unfit” people in order to stop specific undesirable traits from passing to a new generation. In 1907, the country’s first compulsory sterilization law was passed in Indiana, and targeted “confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles, and rapists.” The law was struck down in 1921 but later reinstated in 1927; the second law targeted the “insane, feeble-minded, and epileptic” and stayed on the books until 1974.

______________________________________________________________________________________