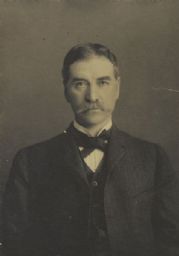

Dr. Harry Hummer, superintendent of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, absorbed any number of inspections conducted by the Indian Service. Unless recommendations fell in with his own desires (such as recommendations for new buildings and equipment, for example), he seldom changed any of his practices to accommodate findings. Hummer was faulted early on for “managing from his desk” instead of getting out of his office and into the wards, where he could see and supervise his staff and patients. Apparently, he was still managing from his desk in 1927.

In a memo to employees written in January of that year, Dr. Hummer told them that he had been “criticised by Dr. Emil Krulish, the Medical Inspector for this district, for the honor system which I have had in effect at this place for many years past.”

Hummer told employees that he would now be making more frequent inspections to see if they were carrying out his instructions. He had “already discovered that collectively you are off your wards entirely too frequently.”

Hummer told his staff that they would need to give him a satisfactory reason for being off the ward; for the first offense they would receive a warning, and for the second, “summarily dismissed from the service.”

Employees had to sign and date that they had read the instructions. However, since conditions continued to deteriorate, it seems improbable that Hummer actually followed through with his promised crackdown.