St. Vincent's Institution for the Insane, near St. Louis, Mo., circa 1910

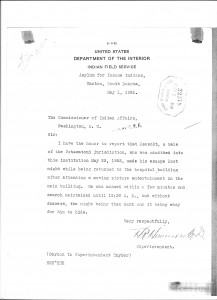

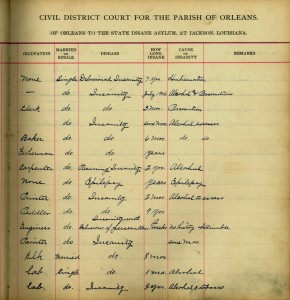

Many people involved with “Indian Affairs” made reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, who then consolidated them into a report to the Secretary of the Interior. These people might be inspectors, superintendents of schools, reservation superintendents, Indian agents, and so on. Though my own research was largely confined to the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, I found interesting material adjacent to the entries I actually needed to see. A 1907 report from the Indian Inspector for the Indian Territory provided this information:

The act of April 28, 1904 . . . provided that insane Indians should be sent to the Government asylum at Canton, S. Dak. In accordance with this act a contract was entered into with St. Vincent’s Institution for the Insane at St. Louis County, Mo., . . . providing for the care, maintenance, and support of insane persons from Indian Territory, not Indians, at the rate of $300 per annum, which includes all necessary medical attendance, nursing, treatment, medicines, clothing, washing, and board and care for the insane persons in a proper and humane manner.”

Per annum cost at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was $366 in 1907, and an extraordinary $394 in 1908. This may not seem like much today, but the overage was almost 20-25 percent higher than the government allowance for non-Indians at St. Vincent’s. In 1910, the average annual cost for the institutionalized insane throughout the country was $175–which makes the figures from Canton seem especially high. Dr. Hummer, Canton Asylum’s superintendent, knew his figures were high and struggled constantly to get them down.

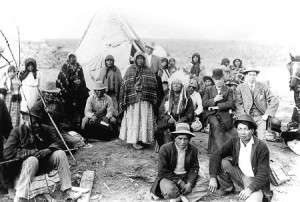

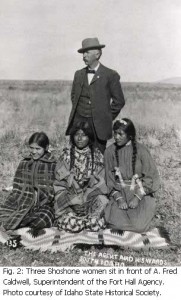

Three Shoshone Women and A. Fred Caldwell, Superintendent of the Fort Hall Agency, courtesy Idaho State Historical Society

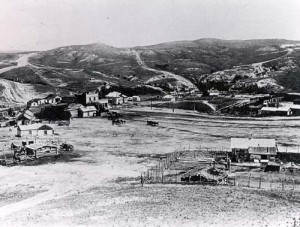

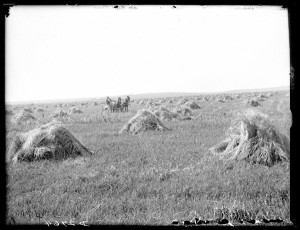

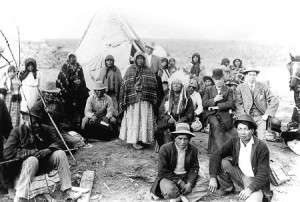

Indian Agent Heinlein Issues Blankets, Tents, and Clothing to the Paiutes in Exchange for their Land, courtesy Benton County Museum, Oregon

______________________________________________________________________________________