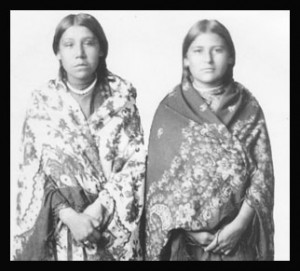

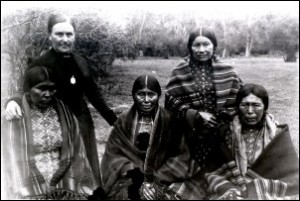

Presbyterian Missionary Kate McBeth and Nez Perce Students, late 19th Century, courtesy Idaho Historical Society

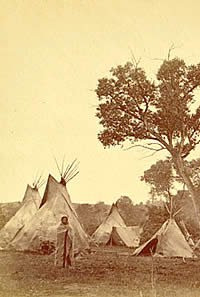

Besides encouraging native peoples to take up farming, white settlers believed that introducing Christianity would help “civilize” Indians (see last post). Federal policy encouraged missionaries to enter Indian territories to spread both the gospel and white culture. By the 1820s, missionaries were active as far west as Oklahoma, and by the 1850s, had established churches, schools, and mission stations among the Cherokee, Comanche, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and many other native peoples. The government did not always observe a strict separation of church and state, since they considered Christian missionaries effective ambassadors of white culture, and actively encouraged their involvement in reservation life. In 1869, federal officials instituted the Peace Policy, a church-led assimilation program based out of reservations. These and similar efforts fell in line with the prevailing notion that America held a unique position in the world because of its Christian, democratic roots, and needed to spread its ideals across the continent.

For the most part, missionaries were undoubtedly convinced that their work would better both the physical and spiritual lives of Indians, and Native Americans did not always reject Christianity out of hand. Various Native American belief systems held commonalities with Christianity, and Native Americans tended to be spiritually inclusive. As a result, they could accept appealing parts of Christianity without rejecting their own traditional belief systems. In unfortunate contrast, Christian missionaries wanted Native Americans to abandon their heritage and culture completely. This adversarial stance guaranteed that Native Americans would suffer almost continually for practicing their own religion.

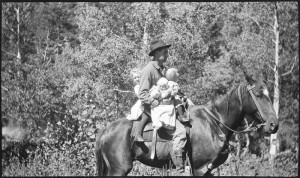

Reverend Arthur on Horseback With His Three Children, courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

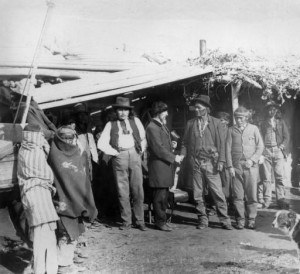

Chief Black Horse Shaking Hands With Missionary, Promising Friendship, between 1880 and 1910, courtesy Library of Congress

______________________________________________________________________________________