Lewis Hines Photo of Oyster Shuckers in Port Royal, South Carolina, early 1900s, courtesy Library of Congress

When reformers first began to champion the use of insane asylums in the 1830s, these institutions really did tend to operate as the havens they were meant to be. Life was harsh everywhere for most people: there were few protections for workers, public aid for the weak or disabled scarcely existed, and bodily comfort might mean no more than a slice of bread and a straw-filled sack to sleep on.

It was an age when a professor at the Paris Faculty of Medicine could safely state: “The abolishment of pain in surgery is a chimera. It is absurd to go on seeking it . . . Knife and pain are two words in surgery that must forever be associated in the consciousness of the patient.”

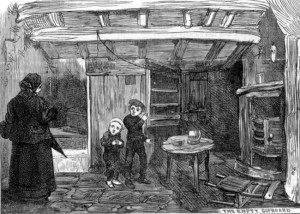

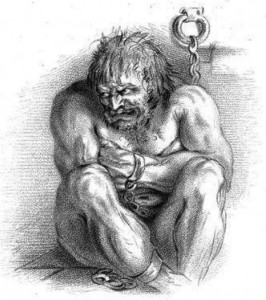

When surgeons scoffed at the idea of easing pain for (presumably) paying patients, what comfort could lunatics–who supposedly did not feel pain, cold, or hunger–expect? When Dorothea Dix began her crusade to provide compassionate care to the insane, she wrote graphically about the filth and misery she found in jails and outbuildings where the mentally ill were held as prisoners. Once asylums were established, however, these patients could expect decent food, clean bedding, warmth and ventilation, and human attention.

Conditions deteriorated quickly as families filled asylums with relatives they either did not want or could not handle. Some asylums became little better than the dark and filthy jails they had replaced, and certainly did not help their patients to recover. Coming full circle, reformers again began to agitate on behalf of the insane–to release or “de-institutionalize” them.