No asylums had an overabundance of staff, and asylum administrators walked a fine line between doing what was necessary and convenient for their personnel, and what was best for patients. A 1906 article in The American Journal of Insanity discussed the pros and cons of hiring night nurses and unlocking patients’ doors at night. The superintendent of the Missouri State Hospital No. 2 wrote that after doing away with the system of night watches–who passed through the halls and wards once an hour–and going instead to a full staff of night nurses, the incidence of suicide immediately dropped. Patients were also much more comfortable and quiet.

“The idea of locking one, two …seven or eight patients in a room or dormitory, expecting patients to remain quiet, to sleep well, and to get well, is not only absurd,but is inhuman,” Dr. C. R. Woodson wrote. “The morbidly suspicious should certainly not be blamed for imagining that there was danger when locked up in a remote room of an institution with those who may or will domineer over them.”

Woodson went on to say that even violent patients responded well to the unlocked door policy. “The fact that a patient can get up and go to the toilet-room when he wants to, get a drink of water, or even get up and look down the hall, is a source of satisfaction; it makes him less rebellious, less obstinate, and less violent.”

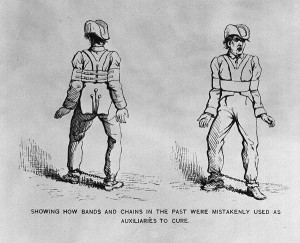

Woodson was doubtlessly correct, and it is strange that it would have taken practitioners in the field so long to circle back to Philippe Pinel’s discovery in the early 1830s that removing chains from the madman did much to subdue his violence.