I have written a book called Vanished in Hiawatha: The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians

about the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians published by the University of Nebraska Press. I am looking forward to getting this story out to the public, and hope that every reader will discover something new and interesting about the asylum and the era in which it operated.

I stumbled upon the Canton Asylum story quite by accident, while researching the topic of involuntary commitment to madhouses in the 19th century. I was astonished to discover that a place like Canton Asylum had existed, and I immediately began digging for more information.

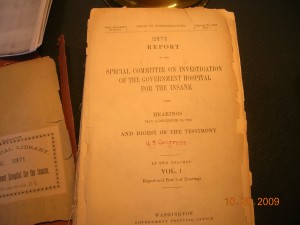

I’ve reviewed thousands of pages of primary documents in the National Archives and Library of Congress concerning Canton Asylum, the treatment of Native Americans, government policies, and other related topics. I’ve also reviewed dozens of articles in the American Journal of Insanity (which changed its name to the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1921), pored over inspections, reports, and statistics from the era, and discovered information about key figures from many other primary sources.

I invite you to read my blog, which will not duplicate information found in the book (except for some of the barest facts). Instead, I concentrate on information about the era, people, and places that affected the establishment of Canton Asylum.

I would like to thank everyone who has followed my blog for these past few years. I created it to support the book I was writing, Vanished in Hiawatha: The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

PLEASE NOTE: I am beginning a new research project and will no longer post to this Canton Asylum website. Instead, I invite you to follow my new blog called Healing, Hell, and the History of American Insane Asylums

This site will support a new book I am writing which will contain interesting information about asylums in the United States and the history of mental health treatment. I’m excited about it and hope you will be, too.