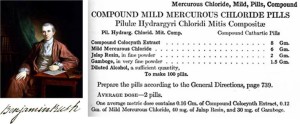

The change in attitude between the old-style treatment of the insane and the new moral treatment’s philosophy (introduced by Pinel and Tuke) cannot be emphasized enough. Though some of the worst cruelties and neglect had fallen out of favor by Benjamin Rush’s time (December 24, 1745 – April 19, 1813), the man considered the “Father of American Psychiatry” believed that any physician treating an insane person had to first dominate that individual–usually through fear. Hence, threats and coercion were considered perfectly acceptable ways to gain the necessary control and authority.

One of the pioneers in American psychiatry, Dr. Amariah Brigham (December 26, 1798 – September 8, 1849) urged a completely different style of treatment. He and others of like mind developed the (then) modern insane asylum, which was capable of putting their ideas into action. For instance, Brigham believed that mental occupation was useful in effecting a cure, and suggested engaging patients’ minds in learning. He urged every institution to have something of a school within it, containing books, maps, scientific apparatus, and so on. Patients could learn reading, writing, drawing, music, arithmetic, history, philosophy, etc. The instructors in these schools would engage with patients constantly: they would teach, of course, but would also eat with patients, join them in recreational activities, and generally become their comrades. This type of engagement was for patients who were curable.

For those who weren’t (the chronic insane), manual tasks such as farm work, basket-weaving, sewing and embroidery, painting, printing, shoe-making, etc. would go a long way toward engaging patients’ attention and re-directing their thoughts in a positive manner. The physical work would also preserve their health by keeping them active.

In either type of patient, this kind of moral management, with its regular schedule, mental diversions, and lack of coercion, could be expected to help patients much more than the fear-based management of preceding philosophies. If the public had provided enough money to implement these programs effectively, the early hopes of the new psychiatric profession might have been realized.