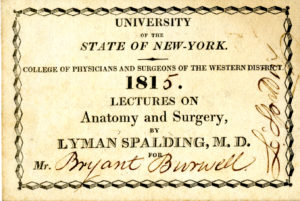

Early physicians were prepared to handle a variety of medical cases, and rural practitioners often took on mental illness as well, if their territories were too far away from asylums for treatment. They had a difficult and uncertain occupation, however, that didn’t necessarily provide a good living. We may be used to seeing doctors earning comfortable salaries today, but that wasn’t always the case.

Rural doctors could not set extraordinarily high fees for their work or they wouldn’t have been able to find and keep patients. But, the time-consuming trips they made to see patients (during the age of house calls) prevented them from seeing many patients on any given day. Few patients, of course, meant meager salaries. Earnings were all too often along the lines of the doctor in 1849 who billed a patient $12 for services–but then deducted two dollars in exchange for two bushels of buckwheat.

Because it was so difficult to earn a living as a full-time physician, many doctors took on second jobs. During the early 1800s in Burke County, North Carolina, doctors held second jobs ranging from Superior Court clerk, to school teacher, to hotel operator, to farmer, in order to supplement their wages as physicians.

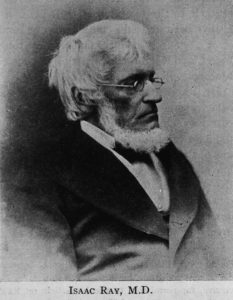

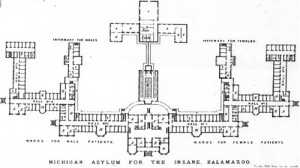

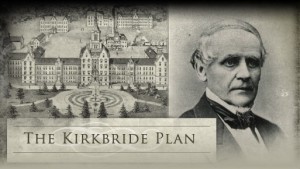

It is no wonder that a position as an asylum superintendent would be so attractive to medical men, and so jealously guarded by physicians who were alienists. Because they could squeeze out competition, asylum superintendents enjoyed decent salaries and pleasant places to live. Though they didn’t own the homes or living areas they received on the asylum’s grounds, the buildings were grand and elegant (at least at first), and the grounds beautifully landscaped. Such a situation was much better than the salaries and living arrangements available to many other physicians outside the field.