Images of Different Types of Insanity by J.E.D. Esquinol, courtesy Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.u

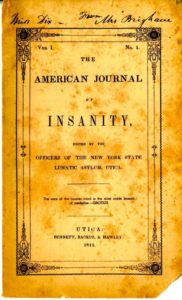

In the April, 1879 issue of the American Journal of Insanity, Dr. Judson Andrews gave some tips for family physicians to use in monitoring the possible development of insanity in their patients (see last post). The physical symptoms were disturbingly commonplace, but Dr. Andrews seemed to hit a bit nearer the mark when he described certain mental signs that might indicate the development of insanity. (In general, he thought these mental symptoms would develop after the physical ones.)

— Emotions might be exaggerated (a little or a lot) or the person might be unable to control expression of the emotion even when he tried.There might not be a cause for laughing or crying in a situation, or the reaction might be out of character for the individual.

— Depression might develop, either as a loss of spirits or a “shading off from the natural cheerfulness of disposition.”

— Patients could experience “forebodings of some indefinite, indefinable evil impending, from which no way of escape lies open.”

–Later, patients would begin to be overly introspective; in reviewing their actions, they would judge themselves far too harshly and negatively.

— Patients could develop difficulty making decisions about simple tasks (like what to wear) and important ones alike; any course they decided upon then yielded to “agonies of doubt” or vacillation.

Other changes might be in personality, dress and personal appearance, and “exaltation or exaggeration.”

Unfortunately, many of these symptoms could develop so slowly they would be hard to detect; in other cases they might just be an intensification of the person’s normal personality and also hard to spot. At least, though, concluded Dr. Andrews, insanity had lost its mystery and dread, and “the insane man stands forth simply as a sick man: one, who by reason of cerebral disease, is unable to use his brain.”

This viewpoint was undoubtedly kinder than the fear and judgment insanity had faced in the past.