People who realized they were having problems coping with life often voluntarily sought cures for their mental distress. Catharine Beecher, sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and later co-author with her of a very successful book entitled American Woman’s Home, or Principles of Domestic Science (1869), found the rigors of earning her living overly taxing. When she was twenty-three years old, Catharine supervised a school with 160 pupils, many of them boarders. After ten years of school-teaching, “the nervous fountain gave out entirely,” Beecher said. “I could neither read, write, or converse, nor even bear to hear conversation.”

Beecher traveled and consulted numerous medical men, who tried various remedies without success. She took pills, underwent galvanism (in which electrical pulses were applied to contract her muscles), visited a clairvoyant, and took the Water Cure.

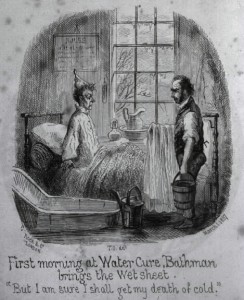

She was wrapped in a wet sheet “at four in the morning,” and kept in it for a few hours before being plunged into a cold bath. Then she had to walk as far as she was able, drink several glasses of cold water, stand under water falling from a height of eighteen feet, drink more water, and so on. She was wet all day.

Beecher related that she spent over ten years under various types of medical treatment, often returning to a mild water cure as the best restorative. She met many other women at these water cure institutions, and began to believe that American women were not as healthy as they should be.

Beecher exhibited periods of extraordinary energy and productivity during her lifetime, and it could be that water cures gave her a form of “time out” to rest and assess her work. She made women’s health a great priority, and gave women common sense tips for dress and diet, as well as advice for efficiently running their homes. Unlike so many cases, Beecher’s treatments for her her mental maladies were voluntary, rather than coerced.