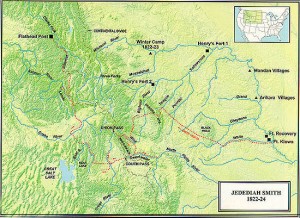

Who were the men who pushed westward (see last two posts) to create both the foundation for a “frontier thesis” and the reality of American exploration and expansion? Among the earliest white explorers were mountain men like Jedediah Smith, who answered an ad in the Missouri Gazette & Publ1c Advertiser in 1822: “The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years.”

Men like Smith were recruited by fur-trapping companies and other businesses that wanted to establish trading posts in new territory. Few men kept records of their journeys, with the exception of Smith. He kept a journal as early as 1826, and his writing is rich in detail about the conditions and people he encountered. On one excursion in search of beaver, Smith wrote that he saw unusual “Black tailed hare” which were darker colored and smaller than the common hare. On another trip in 1828, Smith wrote that one part of a mountainous area was so rough and rocky that it took him four hours to travel one mile. When his party finally camped, he saw that the steep hills beside them were covered with oak and pine. He also saw a tree he had never seen before. “The largest were 1 1/2 feet in diameter and 60 feet high. The limbs were smooth and the bark snuff colored.” Smith wrote that the tree was in bloom and that Europeans in his party called it Red Laurel.

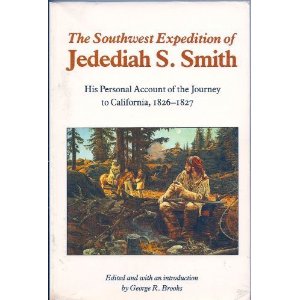

Smith’s journals were lost for many years, but have been discovered and reprinted.

______________________________________________________________________________________