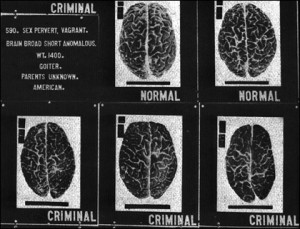

One of the reasons eugenics laws were so disturbing is because their targets were so loosely defined.

Harry Laughlin’s Model Eugenical Sterilization Law in 1914 spelled out just how nebulous the so-called “undesirable” element of a population could be. He proposed to authorize sterilization of what he called the socially inadequate–and the list of these people was long and frightening.

Laughlin, a leader in the American eugenics movement and director of the Eugenics Record Office from 1910-1939, particularly targeted men and women supported in public institutions like prisons and mental hospitals.

His sterilization law included the feeble-minded, insane, criminalistic, epileptic, inebriate, diseased, blind, deaf, deformed, and dependent. The latter could then include orphans, the homeless, and paupers.

Even at the time, it should have been apparent that too many people fell into these wide categories of “undesirables.” And even though proponents of the eugenics movement falsely believed that many conditions were inherited that we know today are not, people of the time surely had observed that an orphan could develop into a model citizen or that a blind mother or father didn’t necessarily pass the condition on to their children.

Even if eugenics had contained merit, decisions about who should and shouldn’t be sterilized were based on opinion or arbitrary distinctions rather than any kind of solid criteria. Over a dozen states had laws that called for the sterilization of criminals, for instance, but which criminals could be sterilized had little rhyme or reason.

Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas struck down an Oklahoma sterilization law in 1942, noting that a three-time chicken thief could be sterilized while a three-time embezzler could not. Douglas noted that there was no basis at all for believing that “the inheritability of certain criminal traits follows the neat legal distinctions which the law has marked between these two offenses.”

Yes, it could certainly be a sad existence at any asylum. Unfortunately, so many patient records everywhere have been destroyed or lost that it would be difficult to get a realistic idea of an individual patient’s stay.

I just learned that my uncle was “hospitalized” at the Cherokee Institution in the early 1930s. The family never talked about him and growing up I guess I assumed he had died. Now I wish I had asked more questions and I am sad to think of how he might hae been treated there.