Cheyenne-Arapaho Ration Card Used During the Time of the Land Run, courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Winter had always been a time of scarcity for both agricultural and nomadic peoples. Even when crops were good and supplies safe, winter generally meant fewer food choices and dwindling stores of edibles that could not be replenished until spring arrived.

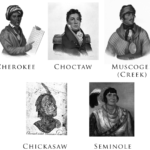

Native Americans faced extreme threats to their food supply by the twentieth century: they had been pushed to unproductive reservations; they were dependent on rations supplied by the federal government; and they did not have the political power to fight for better conditions.

To make matters worse, such food as the federal government thought fit to dispense arrived via the management of bureaucrats and contractors who could be incompetent, indifferent, corrupt, or all three.

Even the best contractors could not deliver food until Congress had appropriated funds for them to do so, and Congress could delay the passage of appropriations for any number of reasons. When food finally did get through, it could be spoiled, of poor quality, or so strange to the recipients that they couldn’t or wouldn’t eat it.

Even if they had been plentiful and unspoiled, federal rations were not particularly wholesome or tasty; they consisted primarily of lard, flour, bacon, sugar, coffee, and beef. Farming was supposed to supply all other food needs, but never did since reservation land was so poor. Rampant hunger and poor health among Native Americans was the inevitable result.