Few townspeople liked Dr. Harry Hummer when he first came to Canton, primarily because he was replacing the very popular former superintendent of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, Oscar Gifford. However, Hummer eventually began to fit in and the Canton community stood shoulder-to-shoulder with him when the asylum was threatened with closure.

On September 28, 1933, the front page of The Sioux Valley News proclaimed that Sunday would mark the 25th anniversary of Hummer’s stewardship at the asylum. The paper also mentioned the community’s hope that he would continue in place, along with the asylum, in order that he and his wife could “remain active and interested residents in the promotion and welfare of Canton and Lincoln county and the state of South Dakota.” No mention was made of the asylum’s Indian patients.

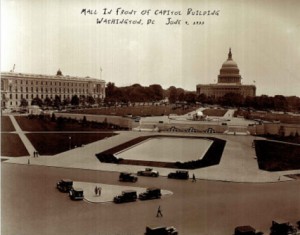

The newspaper’s real interest and concern become especially clear on another page of that same issue, where it discusses the “first four rounds in the Indian battle of John Collier et. al vs. G. J. Moen, et. al.” The first round came when “Collier darted from his corner in a surprise attack and led with a right to the jaw calling in the Indians to Washington.” The second round found his opponents securing a ten-day stay. Moen went to Washington, D.C. in the third round, and “jabbed in another five days stay which busted up Collier’s plan of attack.” Before Collier could recover from these blows, said the paper, “Moen slipped in a haymaker to the jaw in the form of a federal court injunction, which tied Collier’s hands, sent him rocking on his heels and left him gasping for breath, amid the cheers from the local gallery.”

The paper concluded triumphantly that, “After all this fracus, we’ll bet John Collier got out his map and looked to see whether Canton was in South Dakota or South Dakota in Canton.”

Actually, all of the federal investigations of the Canton/Hiawatha asylum (>10 investigations) were triggered by complaints initiated by Canton residents who worked at the asylum. Those Canton residents advocated for better conditions for the asylum inmates, even though they knew, if they did so, they would lose their jobs. That took a great deal of courage. After WWI, farm values had plummeted, and by 1920, South Dakota farms were operating at a loss. By the time the asylum closed, 35,000 farms had been lost to foreclosure, and 71% of the state’s banks had failed. In addition, South Dakota had become a Dust Bowl state, ravaged by drought, fierce winters, hordes of grasshoppers, and dust storms. More than 50,000 residents left the state. At the time of the asylum’s closure, 40% of South Dakota’s families were on relief — South Dakota had the highest percentage of people on relief in any state at that time. The business community in Canton and the South Dakota politicians didn’t want to lose nearly $750,000 (2017 dollars) in annual asylum funding from Washington DC during the Dust Bowl. But the Canton residents who worked at the asylum had the courage to speak up, knowing they would their jobs in the middle of an economic nightmare.

Currently, local Canton historians and the Keepers of the Canton Native Asylum Story are interviewing community elders and staff family members to learn why/how the asylum staff had the courage to risk their families’ survival for the sake of the Native Americans incarcerated in the asylum.

G.J. Moen and the other Canton business leaders were severely reprimanded by John Collier when they went to Washington DC in the Fall of 1933 to lobby for the survival of the asylum. Ultimately, the Canton business interests lost the court battle in December 1933. Hummer had been fired in October 1933 and charged with misfeasance, malfeasance, and incarcerating sane Indians. Hummer and his wife moved to Sioux Falls where he opened a private practice, worked at the VA hospital, and faded into obscurity.