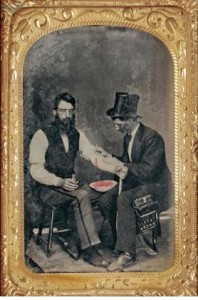

Older methods of curing illness often included bloodletting, the practice of purposely lancing a patient’s flesh in order to get blood flowing. Quantities extracted could be quite small or surprisingly voluminous, depending upon the individual doctor’s beliefs about its effectiveness. Many doctors nearly bled their patients to death, and this type of aggressive, “heroic” medicine fell out of favor during the nineteenth century.

The idea behind bloodletting was that the practice allowed the cause of an illness to get out of the body through the blood flow. Like other cultures around the world, Native Americans also believed in bloodletting. The Chippewa thought that doing so would remove “bad blood” and relieve a number of conditions. A shaman or other practitioner would make a small gash in the patient, with a knife or sharpened piece of porcelain. A gash in the elbow could treat a strained back or arm, while a small incision in the temple could treat headache or non-violent insanity.

Rather than being the traumatic experience many patients experienced at the hands of European or American doctors (who often took from 16 – 30 ounces of blood), Chippewa bloodletting only allowed about a teaspoonful of blood to escape. The small wound could then be closed by placing a poultice, chewed bark, or chewed tobacco over it.