Print of Assassination Attempt, which appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 16, 1881, courtesy Library of Congress

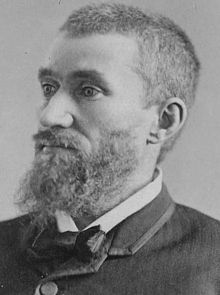

Charles Julius Guiteau shot President James Garfield at the Pennsylvania railroad station in Washington, DC on July 2, 1881. He did not try to escape and was apprehended on the spot; when the president died twelve weeks later, Guiteau went on trial for his murder. The public was fascinated and the trial became something of a media circus, with Guiteau’s behavior as avidly reported as the points made by the attorneys for the prosecution and defense.

Guiteau interrupted witnesses and lawyers, spoke of himself as an instrument of God, and generally behaved in an erratic manner. His defense attorney pleaded insanity for Guiteau, but insanity was a difficult defense at that time. Under the strictures of what was called the M’Naghten rule, the government only needed to show that the defendant understood the consequences and the unlawfulness of his conduct. Guiteau had made it clear that he did know it was illegal to shoot anyone, and that he had expected to kill the president.

Guiteau’s family had a history of insanity, which at that time, meant a great deal. A number of medical experts testified to Guiteau’s present insanity, including Dr. James Kienarn, a Chicago neurologist. He stated that a man could be insane without suffering from delusions or hallucinations, and that Guiteau was clearly insane. New York neurologist Dr. Edward C. Spitzka wrote that “Guiteau is not only now insane, but that he was never anything else.”

Other alienists saw Guiteau quite differently, particularly since the assassin knew the difference between legal and illegal action. The most famous alienist for the prosecution was Dr. John Gray, superintendent of New York’s Utica Asylum and editor of the American Journal of Insanity. Gray believed that much of insanity resulted from physical causes such as lesions on the brain, and said that Guiteau was too rational to be insane. He was depraved, to be sure, but not insane.

Guiteau offered his own closing arguments, which included singing “John Brown’s Body.” He told jurors that he was divinely inspired to kill the president, and that the “nation would pay for it” if he were found guilty. The jurors deliberated an hour and found Guiteau guilty. He was hanged on June 30, 1882. Since his death, many doctors have since concluded that Guiteau really was mentally ill.