Utes, Indian Agent and Others at Ft. Duchesne in 1886, courtesy U.S. Signal Corps

In 1898, forty Indian agents answered an inquiry from the Committee on Indian Affairs concerning the presence of insane Indians within their areas of supervision. Among all forty agents, they found only fifty-five insane Indians and perhaps fifteen to twenty who were “idiotic.” The agents’ replies were very similar:

“I would state that there is now but one insane Indian on this reservation. We have, however, two Indians from this reserve now inmates of the Government Asylum for the Insane at Washington, D. C. I do not think that insanity is any more common among Indians than among whites.” Chas. E. McChesney

“There is only one hopelessly insane Indian on this reservation at present time. One died last winter. There are others more or less weak-minded, but they are not so insane that they can not be cared for in some way by their relatives or Indian friends.” J. W. Watson

“I have about 8,000 Indians under this agency; there is no insanity among them.” J. Roe Young

“I have to advise you that there are 1,283 Indians under my charge at this agency, none of whom are insane, and it is my observation that this affliction is much less common among the Indians than whites.” Luke C. Hays

Senator Pettigrew (who pushed for an Indian insane asylum) was not getting the overwhelming numbers he doubtlessly desired, but he would have been pleased by the agents’ answers to another question that had been put to them. My next post will discuss the latter.

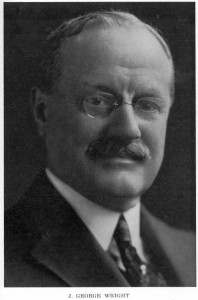

J. George Wright, Indian Agent at Rosebud Reservation, 1889, courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Shiprock Agency Building, New Mexico, circa 1908, courtesy Library of Congress

______________________________________________________________________________________