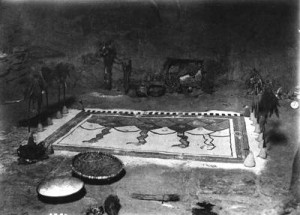

Lokata Sioux Winter Count Showing Smallpox Outbreak, courtesy National Institutes of Health

Smallpox decimated Native Americans (see last post) after Europeans arrived and spread this virulent disease on a population with no immunity to it. However, the disease was not simply accepted and endured. Though native peoples did not immediately connect smallpox with Europeans, they did understand illness and how to treat it.

Native Americans first turned to traditional medical practices to help combat smallpox. Drums, rattles, and incantations helped patients rally, while fasting and dreaming also followed traditional healing ways. Herbs and oils were used to alleviate discomfort. Unfortunately, the common use of the sweat lodge in treatment may have made a patient’s condition worse, since heat and steam caused sweating and dehydration, while cold water plunges may have overly shocked the body.

The Cherokee developed a Smallpox Dance in the 1830s, and other tribes formed curing societies and developed healing rituals. Families eventually stopped their traditional practice of crowding around a sick patient and allowed a quarantine for those with smallpox; people also avoided traveling to places with active cases, and burned (or thoroughly cleaned) homes where someone had died of smallpox.

The smallpox vaccine was available as early as the 1700s, though Native Americans were not routinely vaccinated. When the vaccine was offered, however, many native peoples took advantage of it. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was the official vaccination administrator, but missionaries and traders also urged vaccines. Traders, especially, who cared little for Washington politics and did not need to put white settlers’ needs ahead of their trading partners’, were probably just as successful in helping the vaccination effort as the BIA.

The Mandan Tribe Suffered Greatly From Smallpox

Medicine Man Administering to a Patient, courtesy National Institutes of Health