Ordinary homes during the late 1800s and well into the 1900s had few conveniences (see last post); unlike homes today, a dedicated bathroom was a luxury. A largely rural population typically used an outhouse, which could be indifferently built at worst and an uncomfortable distance from the home at best. Continue reading

Tag Archives: insane asylum attendants

Abuse Was Convenient

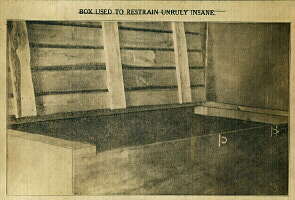

From accounts by former patients, it seems probable that many cases of cruelty and abuse were deliberate. Attendants were often uneducated, uncaring, or of a type who found it impossible to get a job anywhere but in an asylum. Those who enjoyed dominating weak or helpless patients often had little oversight to prevent their doing what they liked; patients reported beatings and punishments which were clearly typical and sustained rather than lapses in judgment or reactions during a crisis. However, attendants often used restraints and other methods of control because they were convenient. Attendants in a short-staffed ward might reasonably believe that it was better to restrain a violent patient or lock him up, rather than let him hurt himself or other patients. Attendants might force feed a patient that they feared would starve because she wouldn’t eat of her own accord. Many attendants undoubtedly did these kinds of things with a perfectly clear conscience.

At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, both types of abuse occurred. A few patients complained of witnessing cruel teasing that would make the targets upset, or of seeing patients treated with unnecessary force or bullied. Attendants more frequently treated their patients badly out of convenience. The asylum was usually short of attendants, particularly under Dr. Harry Hummer. One attendant might have to take care of an entire ward, or at night, an entire building. It was vastly easier to lock patients in their rooms or put them in a restraint, than forgo a meal or get behind on chores for which they would be disciplined if they didn’t complete. Though restraints were supposed to be used only with the permission of the superintendent, the restraints at Canton Asylum were kept in the financial clerk’s office and given out to any attendant who asked for one.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Skimping on Pay

How much attendants were paid (see last post) mattered a great deal to superintendents, and generally not for the right reasons. The public began to exert extraordinary pressure on institutions to accept their afflicted family members, which resulted in overcrowding at nearly every insane asylum in the country. Doctors couldn’t cure patients when they had too many to properly care for, and asylums began to lose their roles as sanctuaries and restorative institutions.

With cure rates down, superintendents had to look for other reasons the public should continue to endorse the use of asylums. One argument was that it was much cheaper to keep patients at an asylum than at home or in jails. Many superintendents prided themselves on how cheaply they could run their asylums, and often compared their rates with unfavorably high rates at other asylums. Salaries were nearly always the largest single expense at asylums, so superintendents had an incentive to hire the cheapest staff they could find. Unfortunately, as Beers pointed out, one could expect very little from an attendant who would work for eighteen dollars a month.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Employee Grievances

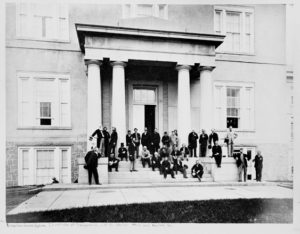

Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, 1870, Male Staff at Entrance, courtesy Brenner Collection, Brynmawr

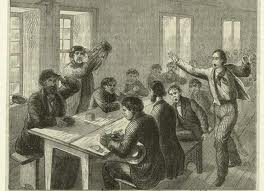

Though it is easy to blame attendants for being frustrated and unkind to the patients in their care, attendants were often frustrated themselves. Mary J. Smith (see last post) told an investigator about her workday: “Her work in the morning is as follows, 6 patients to dress before breakfast–2 paralytics, 1 spastic deplegia, and three that are so crazy they do not know enough to put their clothes on; that she has to wait on tables then after breakfast gives medicine to from 6 to 12 patients, four she has to take to closets (bathroom)–that she has to make 11 beds herself.”

In addition to this daily morning routine, on Wednesday mornings, Smith had to scrub 5 small rooms, one large room, one large hall, three short halls, and a pair of steps. On Thursdays, she had to put the clothing from the laundry away. There were 28 patients in the female ward in 1908, and Smith had charge of 15 of them.

Though there could never be an excuse for mistreating patients, Smithwas undoubtedly harried and overburdened. It would have been tempting to just lock up patients so she could give her attention to some of her additional duties. One consequences of the inspection was that the asylum was authorized to add two attendant postions, one female and one male. Unfortunately, to do so, it had to abolish two laborer positions.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Employee Frustration

Employees at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians didn’t always get along, and the institution’s first big inspection proved that. Dr. Turner had a beef with superintendent Gifford (see last post), but some employees had a beef with Turner.

One attendant in particular, Mary J. Smith, found her work difficult in part because of Turner’s instructions. He did not like to use restraints and wouldn’t often authorize them, but Smith said that she couldn’t do all of her work unless she locked certain patients in their rooms. Her 1908 affidavit stated:

“Doctor had forbidden her to lock certain patients up without his permission . . . ‘he told me if I was doing my duty I would have her (Mary LeBeaux) outside instead of locked in her room, at that time I had locked her in for throwing a cuspidor at me’.” The inspector taking the statement said that “she has marks on her body where the patient has bitten her and has thrown cuspidors at her repeatedly.”

This kind of situation was a quandary for attendants at all asylums: how to handle violent patients without resorting to restraints or reciprical violence. One solution was to call in enough attendants so that the patient could be safely restrained by humans until he/she calmed down. Unfortunately, Canton Asylum had too few attendants for this to be a feasible solution.

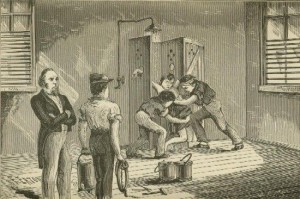

Woman Forced Into Cold Shower, from Elizabeth Packard's book Modern Persecution, or Asylums Revealed

______________________________________________________________________________________

Canton Asylum’s Employees

Like other institutional staff, employees at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians demonstrated a wide range of ability, attitude, and character. Inspectors sometimes complained that employees weren’t always available when needed; sometimes that happened because the employee was shirking his or her duty. More often, however, there just weren’t enough employees to cover all the work that needed doing, plus provide the necessary patient supervision. During the next few posts, I’ll talk about the work situation and some of the employees at the asylum.

One of the first employees to make a stir at the asylum was Dr. John Turner. He was not from Canton, and felt strongly that superintendent O. S. Gifford favored the rest of the employees (from Canton) over him. Turner complained that the attendants often ignored his orders, and that Gifford didn’t back him up. When a patient became pregnant because employees hadn’t followed Turner’s instructions during his absence, he filed a complaint in December, 1906, with the supervisor of Indian schools, Charles Dickson. Turner’s complaint resulted in Canton Asylum’s first major (and negative) inspection.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Attendants Also Drown in Detail

Dr. Hummer found it difficult to keep good help at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. Though part of the problem resulted from Hummer’s bad temper and difficult personality, another part lay in the nature of the work. Attendants in particular had a hard time. They were supposed to be on duty from 6:00 a.m. until 9:00 p.m., though on alternating nights they were allowed to leave at 6:00 p.m. However, they couldn’t leave the premises without Hummer’s permission.

Attendants had a detailed list of 36 specific duties, though they were supposed to do just about anything required of them. A new patient always presented additional work. Attendants were to conduct new patients to their wards and search them for valuables and weapons, make a note of all their clothing, mark the pieces, and then take on the care of the patients’ clothing. They were also to bathe the new patient upon admittance and examine him or her for vermin, marks, or bruises.

The next post will discuss attendants’ daily duties.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Insane Asylums and Economics

Though insane patients were not always embraced by the communities around asylums, communities were often glad to have the institutions near them. Asylums meant jobs, and even small ones could have an economic impact. When the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians opened, residents desired the available positions.

Andrew Hedges, a full-blooded Santee Sioux Indian and the asylum’s first patient, arrived to the delight of the asylum staff on the last day of 1902. They met him at the train station, though this was probably the only time the entire staff turned out for a new patient. The greeters were Mrs. Seely (the financial clerk’s wife) was the matron, Mrs. Turner (the assistant superintendent’s wife) was the seamstress, W.F. More was the attendant, and Hannah Mickelson was the cook.

Canton’s newspaper noted that “Notwithstanding the most specific promises and a petition largely signed by prominent republicans of our city, and county, Mrs. Naylor was not given a position at the asylum.”

By 1927, 21 people were employed at the asylum besides the superintendent. Though Canton residents appreciated the asylum’s jobs, the work was often unpleasant. Attendants came and went with regularity. Dr. Hummer found the lack of trained, dedicated professionals a particularly frustrating aspect of running the asylum.

________________________________________________________________________