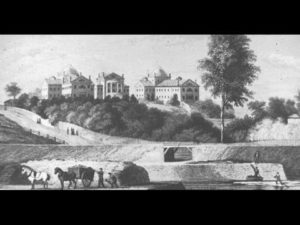

Many people cared about the insane in their midst and tried to do their best by them. Though there were certainly abuses, many of the family and friends who sent their loved ones to insane asylums thought they were doing the right thing or acting in the patients’ best interests. Even after asylums began to lose their initial glow and were seen for the imperfect places they were, many people still felt mentally ill people were better off in them simply because they could receive consistent, professional care.

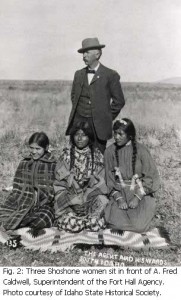

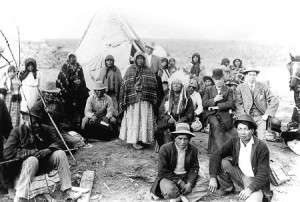

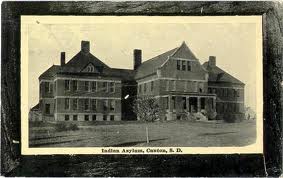

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was representative of its times in this matter. in 1913, the superintendent of the Shoshoni [sic] Indian Reservation asked the commissioner of Indian Affairs to admit Meda Ensign to the asylum. At the time, this asylum was overcrowded, as most were. The asylum’s superintendent, Dr. Hummer, still replied that he would admit her once authorization was given. Many would question this decision, since another patient would only lead to greater overcrowding.

Dr. Hummer did need his headcount to go up so he could supervise a bigger, more prestigious asylum, and typically did not like to discharge patients or reject new ones. However, that consideration very likely wasn’t the only thing on his mind. In his letter to the commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hummer points out the overcrowding, but adds: “If the conditions under which she is living are as bad as portrayed by Superintendent Norris, this authority (to admit Ensign) should be sent me without delay.”

More patients led to overcrowding, which worsened patient care but could justify more money and more buildings so that more patients could be admitted and helped. Superintendents at asylum everywhere juggled these issues, just as Dr. Hummer did. It had to be difficult not to accept patients when it was obvious they would be very poorly cared for elsewhere.