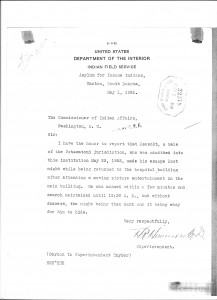

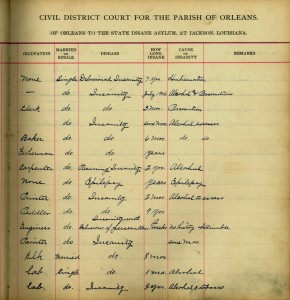

Few patient records from the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians are intact or complete. This is not unusual–many asylums destroyed their records over the years, since early administrators did not see any potentially historical value in them. The Canton Asylum’s records are especially problematic, though, since its superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, was faulted several times for a failure to even keep good records. What never existed cannot very well be found, in many cases. There are a few records that remain, and when patients were transferred to St. Elizabeths after the Canton Asylum closed, staff observed them for a period of time and then summarized the patient’s history and current behavior (see last post). Here is an example of their summation of a patient:

Nesba (Tribe – Navajo)

She was admitted to the Canton Asylum . . . at the request of the Superintendent of Southern Navajo Agency, Fort Defiance, Arizona. The medical certificate at the time stated, “The patient has been in present condition for past two years. Present symptoms, feeblemindedness, dementia.” The patient is a congenital defective suffering with cerebral palsies. . . . During her stay in the Canton Asylum she was infantile in her reaction, subject to tantrums during which she cried and yelled, sang, etc. These periods seemed to coincide with her menstrual periods. At one time during her stay there she was quite destructive to clothing . . . she mimicked people and seemed to delight in teasing other patients.

On her admission here the patient was passively cooperative but unable to stand alone due to her physical handicap. She is mute except for guttural noises which she makes in her throat. No definitive mental content can be elicited. She smiles at any attention received, is quite highly pleased at any effort of others to associate with her.

Other remarks continued to assess the patient’s physical condition and mental status, but staff said it was “impossible to determine whether she is oriented or if her memory is better.” She had been admitted to Canton Asylum in 1924 when she was about 20 years old, so would have been around 30 when she came to St. Elizabeths. Her physical condition probably brought her to and kept her in an asylum.

My next post will give one more patient history.