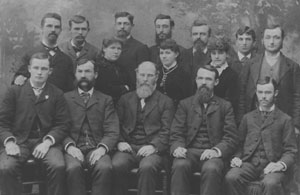

Office of Doctors Charles Hathaway and Ross Bazell, 1902, in Winslow, Arizona, courtesy Old Trail Museum

Medicine in the eastern United States was often hit-or-miss in the early 1800s, but those who pushed to the edge of the constantly changing western frontier were even more apt to suffer at the hands of physicians.

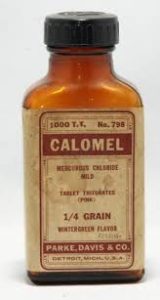

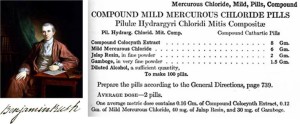

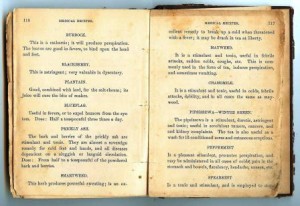

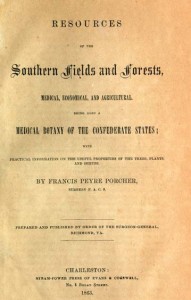

Frontier physicians often took on a variety of jobs: treating horses, pulling teeth, and concocting medicines, in addition to more traditional medical tasks like setting bones and performing simple surgeries. Many physicians were self-taught and consulted a medical manual or two for anything complicated. They relied heavily on substances like morphine; calomel, a compound containing mercury (which the World Health Organization has declared unsafe at any level); and tartar emetic, a toxic laxative containing the carcinogenic, antimony.

Dr. H. M. Greene at Right, in a LaCrosse, Washington Saloon and Pharmacy, courtesy Oregon Health and Science University

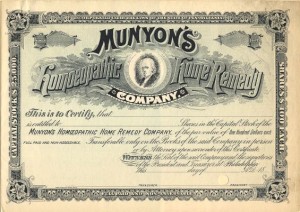

Because they typically had few credentials, doctors in the West tried to impress patients with seemingly exclusive or “inside” evidence of their expertise. Doctors’ offices frequently displayed medical instruments and splints; jars of leeches; body parts bottled in alcohol; and beakers, flasks, and perhaps tubing that implied scientific experimentation or the ability to make mysterious concoctions.

The local populations would be impressed, but they were equally impressed by Native American remedies and tonics touted in traveling medicine shows. The medical profession itself did not have any kind of a monopoly on public trust or faith.