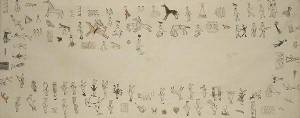

Sam Kills Two, Lakota Winter Count Keeper, circa late 1800s, courtesy National Anthropological Archives

Winter was an important time of year for Native Americans, partly because it allowed time for reflection, repair, and planning. Plains Indians documented their year through “winter counts,” which were pictorial histories drawn on materials like deer hides, buffalo skins, or even paper. A pictograph for the year depicted an important or memorable event for the community preserving it; yearly pictographs were arranged in a spiral or in rows. These pictographs were in chronological order, and served as memory prompts for the group’s oral historian. Individuals could also create their own winter counts so they could remember important events in their lives.

A community’s historian did not arbitrarily decide upon the most memorable event of the year, but instead, consulted with elders to decide what that year’s event would be. The event was not merely important, but also memorable–which means that it was often unique or unusual. A brilliant meteor shower, terrible sickness, great hunts, and so on, would be candidates for a winter count pictograph, rather than an important but annual event.

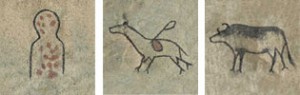

Lone Dog's Winter Count. Smallpox Outbreak 1801-1802, Successful Hunt 1837-1837, and Arrival of Cattle from Texas 1868-1869

______________________________________________________________________________________