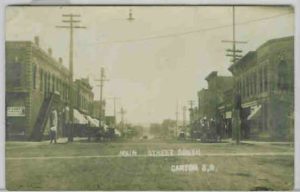

The city of Canton, South Dakota–which existed before South Dakota became a state in 1889–celebrates its 150th year (1866 – 2016) this July.

Canton was founded in a spot called Trapper Shanty. The shanty had been built by trappers Dutch Charley, Bill Tunis, Old Ross, and his two sons, between Beaver Creek and the Sioux River. This small dwelling was an ideal place to capture game, and for several years, this shanty was the only structure in Lincoln County.

Nobody liked the name Trapper Shanty and the townspeople eventually decided to name the settlement Canton for a couple of reasons. Some people thought the spot was directly opposite Canton, China. Others thought it meant gateway in Chinese.

Even so early in its history, Canton’s citizens wanted and expected their city to be important and prosperous. It quickly became a little boom town as pioneers moved through it, or settled and stayed, on their journey west. Canton residents were always ready to embrace bigger and better things, such as an insane asylum built exclusively for Indians. They were sure that this institution—the only one of its kind in the world—would make the city famous. Though worldwide fame eluded the city, its leaders fought to keep the asylum open despite its many critics.